Cleaning Toilets for Jesus

Inside the program teaching submission to capitalism as a divine duty.

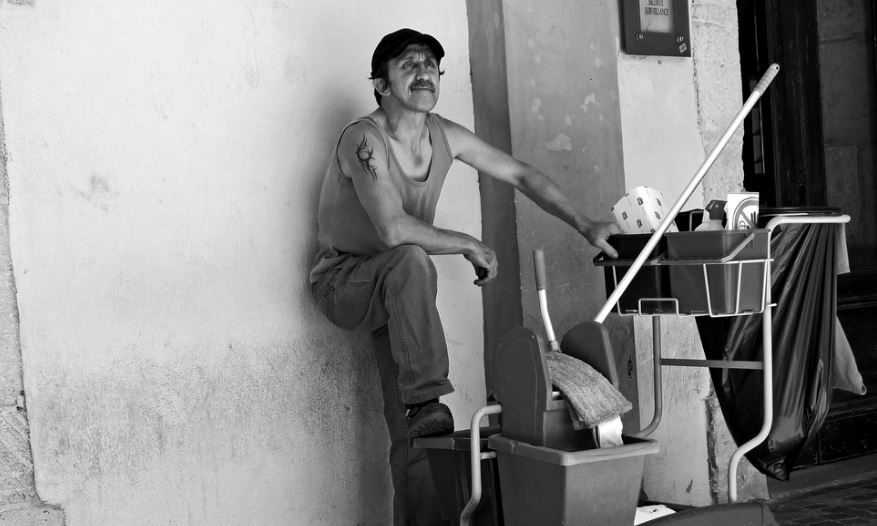

Tom Waterhouse / Flickr

Trump’s “taxpayer first” budget proposal, released last month, not only guts social welfare spending, but expands work requirements for low-income recipients of aid. “If you are on food stamps and you are able bodied, we need you to go to work,” declared budget director Mick Mulvaney.

Making low-income Americans work to qualify for aid has long been couched in the language of personal responsibility, dignity, and civic and moral duty. Mulvaney’s comments during the White House briefing were no exception: “There is a dignity to work,” he declared. “And there’s a necessity to work to help the country succeed.”

While work requirements are widely regarded as darlings of the conservative agenda, few recognize the role that faith-based organizations have played in lending these policies ideological and practical support. Geographer Jason Hackworth terms this phenomenon “religious neoliberalism,” the “ideational fusion” between free-market ideologues and religious conservatives. These two groups, Hackworth argues, are bound through a mutual “faith in the market, faith in the individual, and faith in a small (or nonexistent) government.”

Arguably nowhere is this ideological fusion more prominent than in the faith-based — or, rather, faith-saturated — job-readiness program called Jobs for Life (JFL). Founded in 1996 in Raleigh, North Carolina, JFL is a global nonprofit organization premised on the belief that the local church, given its capacity to mobilize the cant of volunteers, is the untapped and ideal “solution” to the enduring social crises of poverty and unemployment.

Jobs for Life

Through the development of “gospel-centered relationships” with the jobless poor, JFL aims to see “all people working and living for the glory of God.” An article in The Christian Science Monitor, entitled “Today’s hot new career handbook? The Bible,” lauds JFL as offering “a bit of Jeremiah for the jitters, some Noah for uplift, and Joseph for perspective.”

JFL has long been regarded as a model for religious engagement and faith-based activism in the post-welfare era. In 1997, its cofounder was invited to the White House by President Clinton to help plan and promote “welfare-to-work” policies. And in 2000, it became the basis for a Texas lawsuit challenging the legality of using public funds for such an overtly sectarian organization. Judges later dismissed the lawsuit, thereby legitimizing Bush’s later faith-based initiatives.

Twenty years since its founding, JFL has become a significant and firmly entrenched player in the landscape of job-readiness programs. By 2015, its courses were offered in over 347 cities across forty states and seven countries to nearly six thousand individuals each year, mostly in churches, community centers, homeless shelters, jails, and prisons.

JFL’s proliferation thus mirrors two broader trends: the increased reliance upon faith-based organizations for service provision to the poor (as documented, for example, in Jason Hackworth’s Faith-Based and Tanya Erzen’s God in Captivity) and the monomaniacal focus on enhancing individuals’ “employability.”

On the one hand, JFL explicitly frames itself as an idealized alternative to “failed” government programs. In its annual report, the CEO writes, “Today, government programs spend up to $25,000 per person helping someone find a job. And these strategies do not address the underlying emotional and spiritual problems that tear at the fabric of our society … By contrast, we have seen churches and ministries offer a much different solution … and the good news is this strategy costs under $250 per person.”

On the other hand, JFL promotes the priority and preoccupation of the post-welfare, neoliberal state: enforcing work.

“Nothing attacks one’s dignity like a lack of work,” the organization declares. It explicitly criticizes and distinguishes itself from traditional Christian charity, which it frames as focusing on the provision of material goods like food, clothing, and housing. “Without employment,” JFL asks, “how will those in need ever be able to sustainably provide for themselves and their families?” JFL demands that we “flip the list” by prioritizing work. Anything less than a “work-first” orientation is deemed feel-good myopia, even “toxic charity.”

We immersed ourselves in several rounds of an eight-week-long JFL course targeted to homeless men, nearly all of whom were formerly incarcerated, navigating the unforgiving labor market with a criminal history record. The course was taught by evangelical Christian religious and business leaders and took place in the chapel of a homeless shelter in a mid-sized, Rust Belt city with one of the highest rates of poverty in the nation.

As scholars who research and teach on issues of labor and poverty, we were warmly welcomed as observers to and occasional participants in the class. Week after week, for two hours every Tuesday and Thursday afternoon, we followed JFL’s curricular “journey,” participating in the collective prayers, the fellowship, the discussions of biblical stories, and the repeated lessons about “character,” job search strategies, and what constitutes appropriate workplace behavior.

JFL, we discovered, bolsters neoliberal demands for personal responsibility and market submission by placing theological emphasis on work as God’s will and design. It thus demonstrates the extraordinary utility of, and reliance upon, religion for the project of enhancing employability, the “new spirit of capitalism.”

“Hearts and Attitudes”

At the end of the workbook’s second chapter, students are asked to complete several fill-in-the-blank statements under the worksheet title: “Is work a blessing or a curse?”

Why should I want to work?

It is what I am _______ to do.

It is a way to _______ what it means to be made in God’s image.

It is a way to _______ God for the gift he has given men.

It is a way to use the gifts and talents I have been given to:

Serve _______.

_______ for me and my family.

Give to _______.

By instilling within participants this biblical perspective on work, JFL is in the business of cultivating disciples who devote themselves to labor and the Lord. For JFL as much as Ben Carson, then, unemployment and poverty is “a state of mind” easily overcome by shifting one’s outlook.

Take, for example, this lesson, taught by Walter, a captivating evangelical preacher and one of the rotating crew of volunteer instructors:

Like the Bible says, ‘work as unto the Lord.’ You know, when my [boss] wants me to do somethin’ — I’m not talkin’ ‘bout immoral, I’m just talkin’ ‘bout somethin’ I don’t wanna do. I don’t really want to clean the toilet. Well, I’m not cleanin’ the toilet for the boss. According to scripture, I need to work as unto the Lord. I’m cleanin’ it for Jesus.

Here, Walter draws upon a biblical passage to affect an attitudinal shift, reframing submission to the employer (“cleanin’ the toilet for the boss”) as an exalted submission to the Lord (“cleaning it for Jesus”).

As another instructor put it, JFL’s purpose is to effect an internal transformation of “heart[s] and attitude[s],” so that participants move away from thinking of employment under capitalism as “adversarial,” and embrace it as the will of, and gift from, God.

Throughout the course, instructors draw upon the overwrought metaphor of “roadblocks” to refer to the things that diminish our employability and get in the way of our life journey. In one class, for instance, we are told that roadblocks are caused by our own false beliefs.

“What are some false beliefs that can cause roadblocks?” the instructor, Barry, asks.

Edwin, a young, soft-spoken participant, offers the resolute, but vague response: “Don’t trust ‘em.”

“Yeah, don’t trust anybody, right?” Barry affirms, before going on to illustrate how this belief plays out in the workplace. “You know, I’ve had a lot of jobs, and everybody’s screwed me. I don’t trust ‘em. They tell me they’re gonna pay me but they don’t pay me. I don’t trust anybody. That, that all employers are —.” He stops mid-sentence and then concludes, “Don’t work for the man, right? All they wanna do is use me and abuse me!”

“And get rid’a me!” Edwin adds.

“And get rid’a me,” Barry affirms. “But it’s a false belief.” Impressing upon his pupils the basic benevolence of employers, Barry adds, “Everybody’s not like that. That [false belief] could take ya out, right?” He skips ahead in his slides until he lands on one bearing scripture from John 1:10-11, below which is written, in all caps, “GOOD NEWS! WE ARE NOT ALONE.”

JFL endeavors to transform participants’ defensive individualism into willful dependence upon, and submission to, the Lord. It’s curriculum draws from biblical parables to produce “employable” — i.e. faithfully submissive, compliant, and grateful — subjects for low-wage, precarious work.

Attitude of Gratitude

An instructor with slicked-back gray hair named Steve paces at the front of the chapel, reviewing the story of Joseph. Reading from the JFL student workbook, Steve explains how Joseph was taken as a slave for Potiphar, a wealthy Egyptian official.

Anticipating the workbook’s subsequent question — “How did Joseph approach his work even as a slave?” — Steve explains that even as a slave Joseph worked hard and “succeeded in everything he did,” ultimately gaining the respect of his master who later “promoted” him to “manager” of his household affairs. Unfortunately, Joseph, whom the workbook describes as a “handsome and well-built young man,” became an object of lust for Potiphar’s wife. But, as a man of character, he repeatedly refused her advances.

“Everything was going well for him,” Fred, an exceptionally cheerful participant, offers, “until Potiphar’s wife got him in trouble!”

“Those women!” Steve agrees, and laughter fills the room. Spurned, Steve continues, the wife accused Joseph of attempted rape, which, despite his protests of innocence, quickly landed him in prison. But the Lord remained with Joseph, Steve stresses, making him “a favorite with the prison warden,” who eventually put Joseph in charge of the jail and later released him. (Joseph finally became one of the Pharaoh’s wealthy Viziers.)

“Everything he touched went well,” Steve concludes. “And that’s the key part for me. It’s that God is in control. Terrible things happened to Joseph. He faced some terrible circumstances, but God was still in control. Sometimes we make choices and things happen to us at no fault of our own. But it doesn’t matter because God is still in control, and God took favor on Joseph.”

The Parable’s lesson, Steve clarifies to the class, is that Joseph succeeded in life (and the ancient Egyptian job market) because he was able to overcome his “roadblocks” — including slavery and prison — through three commitments listed on page forty-two of the student workbook:

- Total allegiance to God first

- Respect for authority

- Performed with unquestionable work ethic

Several sessions later, Jonathan, an instructor who regularly draws inspiration from his job as a director of human resources, reminds the class about Joseph’s story while in the process of challenging the “victim mentality” (“woe is me”) of the poor and unemployed. “You won’t accomplish anything like what Joseph accomplished if that’s your attitude,” he admonishes the men in the room.

He goes on to describe lazy employees “stealing time” or even stealing office supplies because they’re earning minimum wage and think they should be paid better. Tired of the anger and ungratefulness fueling such petty workplace resistance, Jonathan urges the men to adopt an “attitude of gratitude.”

“Joseph didn’t let anything bother him,” Jonathan continues. “He did what he was supposed to do and whatever his master or his boss told him to do. And then he would get thrown back down again and instead of feeling, ‘Well, I’m entitled . . .’ It all comes back to character!” he exclaims.

A Fair Employer

Brandon, a young and remarkably tanned owner of a local human resources consulting firm, comes directly from the office when he volunteers to teach Jobs for Life. He’s always wearing a suit and tie because, as he repeatedly tells the class, “you never know when a networking opportunity might arise.”

Turning to chapter seven in the workbook, we review the Parable of the Vineyard Workers, “a story,” Brandon reads, “of how a fair employer treats his employees.” Drawn from Matthew 20:1-15, the parable describes a vineyard owner hiring one group of laborers in the morning and another group at five o’clock. “That evening,” a student reads aloud, “he [the landowner] told the foreman to call the workers in and pay them, beginning with the last workers first.” The story continues:

When those hired at five o’clock were paid, each received a full day’s wage. When those hired first came to get their pay, they assumed they would receive more. But they, too, were paid a day’s wage. When they received their pay, they protested to the owner, “Those people worked only one hour, and yet you’ve paid them just as much as you paid us who worked all day in the scorching heat.” He answered one of them, “Friend, I haven’t been unfair! Didn’t you agree to work all day for the usual wage? Take your money and go. I wanted to pay this last worker the same as you. Is it against the law for me to do what I want with my money? Should you be jealous because I am kind to others?

Dustin, one of the students whom the facilitators saw as someone who “gave off a vibe of being a little difficult, bein’ a little hard,” objects: “This is the one story I don’t like in the Bible.” He shakes his head, looking down, pondering the story’s implications. Even though he knows he is supposed to think otherwise, he sees injustice.

“Why is this unfair?” Brandon inquires, eager to correct his pupil with respect to one of the stated take-away points from this exercise: to “understand issues from the employer’s viewpoint before you comment or judge.” Dustin points out that some workers were effectively paid more than the others.

“Why would you allow how someone else is paid to rob your joy, after you agreed to your wage?” Brandon demands. He then admonishes Dustin not to “let external factors come in and destroy what you have with your employer.”

But Dustin presses: “If they pay you less, do they value you as an employee? I’d say no.”

Rather than directly address Dustin’s concern, Brandon replies that there is no reason to get a job if you’re just going to get upset and lose it. Besides, he continues, in the real world “you won’t know why people are paid different wages.” In a dogged effort to instill within his students an “attitude of gratitude” as well as a faithful submission, he instructs: “We have to be happy with what we have and the path we’re on and work with the things that the Lord’s given us.” We can’t, in other words, get occupied with the things over which we have no control. The wages of others, he preaches, “have nothing to do with [your] job and [your] responsibilities.”

Here, a metaphorical parable about equality before God gets transformed into a literal God-given mandate against workers questioning their place in the stratified labor market of modern capitalism.

Cultivating Disciples

On the final day of class, standing in front of the Chapel, Barry announces to the soon-to-be graduates that he wants to share what is “really on his heart.” He asks the students to turn to the conclusion of the workbook and he reads aloud: “Trust in the Lord with all your heart . . . seek His will in all you do and He will show you the way.”

For emphasis, he reads it twice more. Then, he preaches: “You were created by God and work was created by God. Trust in Him for He will show you the way.” In a kind of goodbye message, Barry continues, “Our ultimate hope and prayer is that you make this commitment to the Lord and that you lean on Him and put Him first.”

Barry raises his right hand, holding the JFL workbook above his head. “You could memorize all these lessons and learn them so well that you could teach this class.” He then dramatically throws the workbook down on to the table before him and raises his left hand, in which he pretends to hold another book. “Or you could live by the other book [The Bible].”

Submissive and exploitable workers are not just found, but have to be made. Max Weber documented long ago the critical, though inadvertent, role that religion played in the origins of modern capitalism. But for Weber, “victorious capitalism, since it rests on mechanical foundations, needs its support no longer.” Over time, work and acquisition became “stripped of religious and ethical meaning.”

Combining proselytization with the social intervention of “job-readiness” training, programs like JFL reveal the ongoing power of, and reliance upon, religion as ideological arsenal for bolstering the neoliberal project of enforcing market- and work-compliance. Emphasizing the sacred character of and Christian imperative to work, JFL recasts the employable worker as the faithful disciple and submission to the boss as submission to the Lord.

JFL not only preaches faith in the market, but also faith through the market. Increasingly reified and empowered by neoliberal ideology and policy, “the market” becomes the terrestrial testing ground for achieving and proving one’s faith and supernatural worthiness. For those unworthy, it preaches self-contempt and abasement, casting them out into the hell of indefinite joblessness. Such framing rectifies the fundamental rhetorical contradiction in neoliberal ideology: its urging of individual freedom and entrepreneurial behavior while demanding total submission to the abstract, alien decrees of the market. Through the religious neoliberalism of JFL, the deference to capital becomes the first step toward the entrepreneurial achievement of individual salvation.

The religious right, then, is obsessed with more than just oppressing sexual and religious minorities. It has been and remains dedicated to disciplining the poor and working class. Despite his apparent exceptionalism, Trump’s proposal to further gut welfare in the name of promoting “dignity through work” merely continues the older, bipartisan project of stitching a sentimental veil atop an increasingly soul-sucking labor market.