Criminalizing Anti-Austerity in Ireland

Irish activists won major concessions against water privatization. Now, the state is looking to imprison them.

In November 2010, the Irish government agreed to introduce domestic water charges in return for its €85 billion bailout from the European Union and International Monetary Fund. Meters were to be installed throughout the country, households were expected to pay an extra €500 per year for water usage, and responsibility for water infrastructure would be transferred from local authorities to the semi-state company Irish Water.

These measures came alongside a raft of liberalization policies set out in the IMF’s Memorandum of Understanding, which instructed the government to raise taxes, cut welfare, shrink the public sector, reduce the minimum wage, hand €72 billion to the banks, and promote competition in previously “sheltered sectors” such as law and medicine.

Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael — Ireland’s main political parties, both of which represent the center-right — embraced the Troika program during their 2011 election campaigns. But Labour promised to renegotiate the bailout from a pro-growth perspective. Its manifesto decried the “excessive austerity” of the Memorandum and expressed its “concern about the value-for-money” of establishing new semi-state initiatives.

This “concern” was articulated in its rejection of the water tax — a pivotal feature of Labour’s fiscal agenda, reiterated in public speeches, manifesto pledges, press interviews, and campaign ads. For a population on whom the need for austerity was repeatedly impressed, the resonance of its rejection was enough to increase the party’s vote share by almost 10 percent.

So when Labour jettisoned this stance to join a Fine Gael-led coalition, signing onto large-scale meter installation, the betrayal provoked fury among many of their former voters. An internal party memo from 2010 was leaked, showing that Labour had secretly supported water charges since before the election, and a prominent Teachta Dála (the Irish equivalent of an MP) who once described water as “a basic and fundamental need [which] should not be treated like a market commodity” now told her constituents to “give Irish Water a chance,” remarking that “things change.”

The Water Service (No.2) Bill was pushed through parliament in four hours, and meter installation began in early 2014. By this time, the effects of years of austerity were showing: 30.5 percent of Irish people lived in deprivation, 13.2 percent suffered food poverty, male suicides had increased by 57 percent, while emigration, homelessness and unemployment rates soared.

On top of that, Irish Water was instantly struck with scandal when it emerged that this “cost-saving” utility spent €86 million on consultants and doled out bonuses of 19 percent to staff. Fine Gael’s Environment Minister sparked further controversy by awarding the meter installation contract to right-wing business mogul Dennis O’Brien, whose monopoly over the national press has given Ireland “one of the most concentrated media markets of any democracy” (in the words of an independent report).

The Irish people’s “capacity to take pain,” famously applauded by Finance Minister Brian Lenihan, had all but worn off.

Resistance and Repression

The lack of popular resistance which enabled previous neoliberal reform was quickly dissolved, as years of latent discontent became crystallized in this issue.

Led by an alliance of trade unions, left-wing political parties and grassroots community resistance, a campaign was launched which organized mass protests, the obstruction of meter installations, and an effective boycott movement. It was against this backdrop that Joan Burton, the Labour Party’s leader at that time, faced a hostile reception in Jobstown, a working-class suburb of Dublin where she attended a graduation ceremony in November 2014.

Sixty-one percent of Jobstown families are headed by single parents, whose state allowance was slashed by Burton’s Social Welfare and Pensions Bill — one of Labour’s earliest capitulations to the austerity program. Dozens of people, including recently-elected Anti-Austerity Alliance (AAA) TD Paul Murphy, as well as activists from the republican-socialist party Éirígí, staged a sit-down protest in front of the Labour leader’s car, preventing her departure for about two hours.

In the confrontation, local residents who had voted for Labour only to see their communities deserted expressed their anger. But in the end, despite media sensationalism, the protest petered out to what would have been considered in any other austerity country in Europe a relatively mild affair.

Yet for the past three years, this incident has been exploited to criminalize the Ireland’s anti-austerity movement.

More than forty Jobstown protesters were arrested in dawn raids conducted by large numbers of police. Three of those apprehended were prominent AAA politicians; seven were juveniles between the ages of thirteen and seventeen.

Their files were sent to the Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP), who opted to indict twenty-three activists (including Paul Murphy TD) with charges ranging from “criminal damage” to “false imprisonment” — an offense for which the maximum sentence is life. The defendants were not informed of this decision by any judicial authority; instead, their charges became public knowledge after police leaked them to the media, in a move intended to provoke fear.

The government swiftly denied accusations of “political policing.” It refused to pass official comment on the case, though Fine Gael TD Noel Coonan told parliament at the time that “we are facing what is potentially an ISIS situation” from Jobstown which “must be nipped in the bud.”

While his remarks were patently absurd, they reflect the Irish elite’s sense of fear at the growing power of the water movement.

The Right2Water phenomenon had disturbed what had been, in the Republic, a much-treasured consensual politics, shared between two dominant center-right parties, which had its roots in an economy characterized by Catholic corporatism. Ireland was in many ways a former colony, still struggling for independent legitimation, whose leap from pre- to postmodernity bypassed ideological conflict proper.

This culture of anxious respectability allowed the governing parties, along with the media, to present the movement’s participants as extremists, threatening the statesmanship of Taoiseach Enda Kenny.

In late 2014, the Health Minister branded water charge demonstrators “sinister,” saying, “they break the law, they engage in violence, they spread all sorts of misinformation and what I’m worried about is that it is only a matter of time before someone gets hurt.” Olivia Mitchell, another Fine Gael representative, stated that the Jobstown residents had engaged in “acts of violence and terrorism.”

Their comments were echoed by Kenny himself, who likened the protesters to “hounds after a fox” in a 2014 parliamentary debate. The Irish Independent newspaper followed suit, describing Paul Murphy’s activism as “dog’s abuse… intent on [causing] disruption and confrontation,” while the Irish Times painted him as “a dog chasing a car [it] will never catch.” The national broadcaster also faced protests over its biased coverage of the issue, as local resistance to Irish Water services was routinely ignored or maligned.

Along with the demonizing rhetoric, the Jobstown incident sparked a number of heavy-handed interventions against opponents of Irish Water.

A court injunction banned protest within twenty yards of meter installation, restricting the scope for civil disobedience and prompting the arrest of several Dublin activists. Five were given jail sentences ranging from twenty-eight to fifty-six days, while another was reported to have lost his job over the indictment.

The ruling precipitated an increased police presence at small community demonstrations, with up to forty officers overseeing Irish Water construction work in parts of the capital. Dublin City Council passed a motion condemning the “excessive mobilization” of police in working-class areas. Pepper spray was twice used against picketers; video footage showed police hurling a young woman into an iron post; a sit-in protester sustained face injuries when she was forcibly removed from her local council building; and a “special force” of twenty-five officers was established in Cork with the specific mandate to protect meter installation.

By April, the police had been effectively remodeled as private security for water charges.

A score of North Dublin residents — including left-wing politicians Joan Collins and Pat Dunne — were detained during a meter installation protest and held for hours under the Public Order Act. Collins stood accused of causing “apprehension for the safety of persons and property” by “loitering in a public place.” She responded, “I was simply standing on a public footpath.”

Most those arrested received criminal charges which — though dismissed by judge Aeneas McCarthy on the grounds that “there is a constitutional right to peaceful protest” — intensified the association between direct action and delinquency. By 2015, the number of people arrested at water charge protests had risen to 188. But, when Paul Murphy used the phrase “political policing” in parliament, the chair ruled he was out of order and disabled his microphone.

The leaking of the Jobstown defendants’ charges became the subject of an internal police inquiry in 2015. However, the person delegated to investigate the leaks, Superindendent Jim MacGowan, is the husband of the Garda Commissioner. He is also the head of Operation Mizen, a police sub-unit which phone-taps and car-tracks water charge activists.

McGowan’s team, funded by the State’s domestic surveillance budget, has spent months “monitoring protesters, compiling profiles and gathering intelligence on their whereabouts.” It “closely monitors social media and tracks… the leaders” of the anti-austerity movement, according to an Irish Daily Mail report whose accuracy was verified by government sources.

Court Cases

Last year, the charges against the Jobstown protestors reached trial for the first time. In Dublin Children’s Court a schoolboy (aged fifteen at the time of the protest) was convicted for falsely imprisoning Burton and her advisor.

The prosecution’s main evidence consisted of videos in which the boy led a chant and held a megaphone — actions which, police said, marked the child out as a “ringleader.” While handing down the sentence (a nine-month conditional discharge), the judge remarked that the accused was an “active participant” in the sit-down protest. The boy’s application to appeal the verdict was rejected.

Irrespective of its outcome, the terms on which his case was argued demonstrate an insidious shift in discourse: it was the extent of his participation in the protest which determined the teenager’s guilt, not an evaluation of the protest’s legality.

Resistance to water charges is already accepted as a criminal act. The prosecution must simply provide evidence of involvement (as a “ringleader” or “participant”) to secure a guilty verdict. This precedent has now been set for Paul Murphy TD and his co-defendants.

Before the cases began, Orla McPartlin, the police Chief Superintendent who coordinated Murphy’s arrest, moved to financially asphyxiate Murphy’s Anti-Austerity Alliance. Her decision to block the renewal of the party’s door-to-door collection permit was motivated by a belief it “would be used in such a manner as to encourage … the commission of an unlawful act.” While McPartlin refused to specify what offense might be encouraged, her statement was an obvious allusion to Jobstown.

Meanwhile, it was found that police Commissioner Nóirín O’Sullivan (who publicly described the Burton incident as “unacceptable”) had questioned candidates for the position of Deputy Commissioner about their views on the Jobstown protest. Interviewees were asked to comment on “left-wing political extremism” and “left-wing politicians” in Ireland.

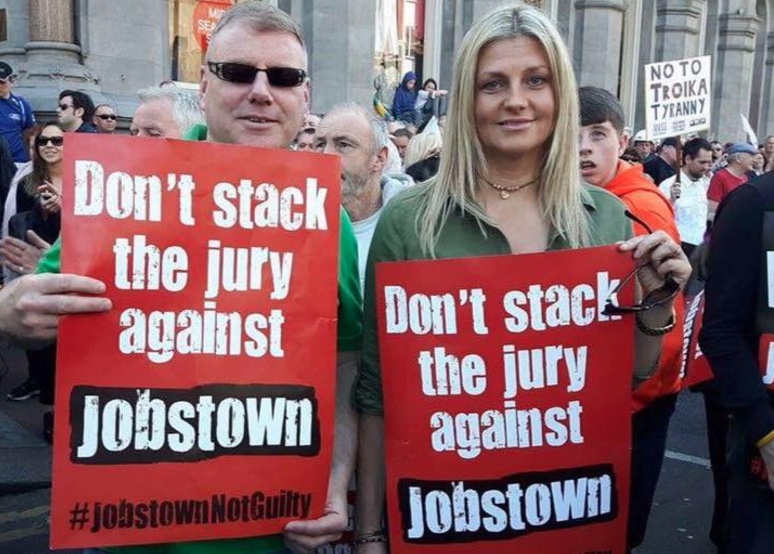

Even so, the state is on shaky ground. The water charges were recently suspended after a three-year campaign and mass popular opposition. There is also an indication that State crackdowns on the anti-austerity movement have been counterproductive. The Jobstown Not Guilty campaign has grown in strength, as evidenced by a boisterous rally held recently in Dublin’s Liberty Hall.

The twenty-three facing trial have received statements of support from international trade unions and campaigners including Angela Davis, Ken Loach, Yanis Varoufakis and Jean-Luc Mélenchon. Noam Chomsky reflected that convictions against the Jobstown activists “would have the effect of criminalizing protest and sending a chilling message to all those who would seek to protest in the coming years.” And, in a supreme embarrassment for Burton, the Northern Irish Labour Party recently passed a motion calling for the charges to be dropped.

In this context, it is unclear whether Jobstown will be an open-and-shut case. The climate of fear engendered by police, media and politicians could be offset by popular sympathy. Which is why, as the trial begins this month, the DPP has tried to skew proceedings in the State’s favor.

Prior to the Jobstown Not Guilty support rally on April 1, a legal appeal tried to block the defendants from publicly asserting their innocence or participating in the anti-water charge campaign.

According to the Irish Times, prosecutor Sean Gillane told the judge that “a matter of serious concern had arisen connected with literature made available around the city and a campaign in respect of the trial … He said he believed the court would find that what was happening to be completely unacceptable.”

When pushed for clarification on this statement, the Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP) office wrote to defense lawyers expressing its intention to “extend the bail conditions to prevent … defendants from making further public comment ahead of the trial” — an effective gagging order. In the end, this most ambitious attempt to criminalize protest was denied.

Jury selection has since become the alternative means of stitch-up. The prosecution demanded that no one from Tallaght (the predominantly working-class area where Jobstown is situated), no one active in anti-austerity organizations, and no one that has ever expressed an opinion about water charges, should be allowed to sit on the bench.

The restriction on political activists is understandable, but the state’s other stipulations signal an extraordinary bid to circumvent kind of problems which the phrase “jury of one’s peers” might present.

Given that Tallaght is the largest district of South Dublin, comprising 14 percent of the city’s population, this blanket refusal to accept its residents is likely to limit the jury’s working class composition. Equally, the rejection of anybody with views on water charges (in a country where up to one in five adults participated in the Right2Water movement) will ensure that jurors are abnormally apolitical — or, rather, that jurors belong to a small sector of Irish society whose privilege allows them to be apolitical.

If the DPP succeeds, such people will probably subscribe to the establishment’s demonization of Jobstown demonstrators — in which case a judge could make an example of these protestors with prison terms, or sanction civil disobedience by suspending their sentences.

Either way, this campaign has already evidenced the extent to which Ireland’s establishment is willing to go in the repression of anti-austerity protest. If it is successful in convicting this latest group of protestors, it is likely to be only the beginning of a much broader attack on political rights.