Class Is in Session

Millennials are better educated than ever. They also overwhelmingly identify as working class.

Bernie Sanders’s deep support among millennials was a surprise for many political analysts. Some have tried to write off the support as youthful exuberance, ignorance, angsty white-male privilege, a profound shared hatred for Clinton, or some combination of these elements.

Others have declared that the Sanders coalition of millennials and working-class voters has little to do with shared interests, let alone a shared class interest; Sanders voters are seen as either idealistic millennials or disaffected white working-class men.

But the facts don’t fit these interpretations. Millennials are not “in bed” with the working class — they are a core part of it. Indeed, more millennials self-identify as working class than any generation in recent history.

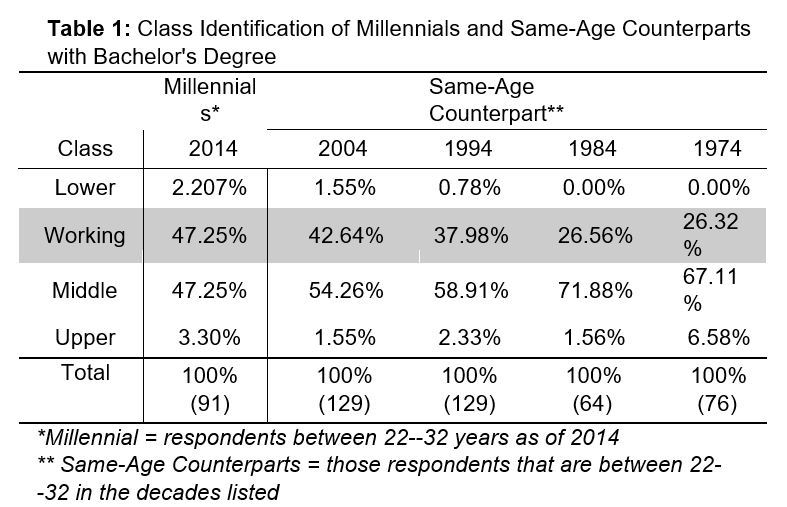

According to the last forty years of survey research conducted by the General Social Survey (administered by the University of Chicago) millennials identify more with working-class positions than any other group. In 2014 some 60 percent of millennials identified as working class.

These figures are striking considering long-held myths about who is middle-class in America. In the popular press, the term “working class” is usually reserved for those with a high school education, working a blue-collar job. And on the surface millennials certainly don’t seem to fit this categorization.

As a cohort millennials are better educated than their older counterparts: Whereas in 1965 only around 13 percent of Americans held a bachelor’s degree, today around 33 percent do, and nearly 40 percent of eighteen- to twenty-four-year-olds are currently enrolled in higher education institutions across the country.

Further, millennials by and large do not work in what would be considered “traditional” working-class jobs like manufacturing or other blue-collar work. Instead they predominantly work in service industries, like retail, hospitality, and health care. So in this respect millennials don’t look working class to statisticians and pundits; instead they are often stereotyped as urban, bohemian, highly literate, and even snobbish.

Assumptions about millennials’ class position are not altogether baseless. They are rooted in complementary sociological theories about the relationship between class and education. Prevailing theories say the markedly higher educational attainment of millennials should allow them access to “middle-class” incomes and occupations.

Historically there has been a strong positive relationship between education and class position; of particular importance for nullifying social origins and climbing the class ladder — so the story goes — is an individual’s ability to achieve a bachelor’s degree. In a landmark 1984 study sociologist Michael Hout “proved” that a bachelor’s degree was the ticket out of the working class:

Education diminishes distinctions based on origin status…The leveling effect of education intensifies as length of schooling increases; the effect of status decreases with increasing education. For men with a college degree, status has no effect on mobility.

So regardless of whether your father worked on an assembly line or on a small farm, if you got a degree in the postwar United States you could effectively eliminate your social origins and freely climb the class ladder.

Another class of theories, less rooted in labor market position and occupational mobility, argue that educational attainment enables degree holders to acquire middle class “tastes” and cultural capital.

Proponents of the “distinction” model argue that because many millennials have received or will receive a bachelor’s degree they, by default, have earned middle-class credentials, namely cultural traits associated with professional/managerial workers.

The relationship between education and class has been so thoroughly accepted that today educational attainment often serves as a proxy for class in much of the sociological and popular literature.

And for much of the postwar history, this causal analysis held up. It was generally true that if you received a bachelor’s degree you would earn more and probably work in a professional or managerial position, rather than as a manual or unskilled worker.

From this perspective the argument is simple: millennials are imagined to be overwhelmingly middle class because they are presumed to have completed university education. How, then, could millennials have any shared interests with the working class, let alone identify themselves as working class?

The paradox is that today millennials are both better-educated and less well-positioned in the labor market than their older counterparts. By the end of the decade nearly 50 percent of millennials will have a college degree compared to just 35 percent in Generation X and only 29 percent of Baby Boomers.

Yet millennials overwhelmingly work in the service sector and the median income of this highly educated group is nearly identical to that of their grandparents at the same age and with less education overall.

Millennials are overrepresented in industries characterized by stagnant or declining wages, with the exception of health care. And ironically, the sector that pays the highest median wages for millennials is the major sector in which the least are employed, the traditional bastion of the working class, manufacturing.

Millennials are also more likely to be unemployed than their older counterparts; even by the government’s very conservative measures over 12 percent of millennials are currently out of work compared to the official national level of around 5 percent.

This brings us to the present question. While educational attainment has steadily increased from the 1960s to today so too has the precarization of labor and the proletarianization of white-collar work. If education does have some mystifying effect on class identification we should see levels of middle-class identification rise with the rise in educational attainment.

However, if even well-educated millennials (those with at least a bachelor’s degree) identify as working or lower class at higher rates than their counterparts in past decades it could mean that the longstanding relationship between class and education is less salient and less static than presumed. And this is exactly what we see.

If we compare well-educated millennials with their counterparts in past decades we see a steady increase in working-class identification. As of 2014 half of all millennials with a bachelor’s degree identified as working or lower class as compared to just 26 percent of their counterparts in 1974.

To be sure subjective class identification does not necessarily reflect actual or objective class positions but there are important lessons to be drawn even from a subjective measure like this one.

First, it suggests that the economic position of millennials does have a genuine bearing on their class identification. In other words, class identification is not the product of some psychological transformation due to attainment of credentials or tastes.

This is where much of the popular narrative gets it wrong. Yes, millennials are well-educated and many may exhibit cultural traits consistent with our image of the American middle class, but millennials are in shit shape economically and through no fault of their own. Millions have played the game by staying in school and getting a degree but they haven’t been rewarded economically.

This material reality seems to inform their class identification. Regardless of whether they (and the population at large) understand working-class to mean blue-collar, pink-collar, or otherwise, the term represents a positional category below middle class.

Choosing that term suggests that many millennials see their stagnant and declining wages, among other signs of economic precarity, and ultimately recognize their class position — a feat in and of itself considering the narrow American cultural understanding for who qualifies as working class.

It is also worth noting that Sanders didn’t “bring class back” — superimposing old fashioned class categories (that no one in the United States subscribes to) onto an old-fashioned politics. It was the fall in real wages, the rise of precarious labor, the proletarianization of white-collar work, the rise in real unemployment, the persistence of underemployment, and the dramatic rise in income and wealth inequality that have brought class back.

These factors have created conditions in which relatively well-educated (and perhaps formerly middle-class) millennials identify overwhelmingly with the bottom half of the class spectrum. Sanders has been able to articulate a politics that speaks to them — a class politics — better than any other candidate.

Secondly, these findings problematize the theoretical link between education and class. The argument for a theoretical relationship between class and education can only be made on the assumption that education will provide access to a limited number of higher-skill, higher-status jobs and that higher education will only be available roughly in proportion to the number of people necessary to fill those positions.

This is not the case. The expansion of the US higher education system from the 1960s to today has not coincided with a concomitant expansion of high-skill, high-paying jobs.

Theoretically there is no good reason to assume that education has an intrinsic relationship to class or social mobility under capitalism. Just because education provided a pathway to mobility in the past doesn’t mean it always will.

Indeed, it appears that the millennial cohort realizes this en masse in light of their inability to achieve the material comfort associated with middle-class American lifestyles (like the lifestyles of their parents and grandparents) despite many of them holding bachelor’s degrees or higher.

Of course at the end of the day, over half of all millennials do not hold bachelor’s degrees. The stereotype of millennials as overeducated entitled urbanites helps to erase the reality that most people in this age cohort in fact still only hold a high school degree.

The chances of these lesser-educated millennials getting a well-paying job gets worse by the minute. While education is no longer the ticket out of the working class that it once was, high school graduates have a much harder time competing for higher wage jobs against their credentialed counterparts — a competition that ends up forcing the wages of both groups down.

But even highly educated millennials face problems traditionally associated with working-class living conditions: unemployment, underemployment, an unpredictable work life, high levels of debt, and stagnant wages. Many college-educated millennials recognize this and that recognition has led to their overwhelming identification as working class — despite their degrees and so-called cultural capital.

This simple fact clears away the confusion surrounding the Sanders phenomenon. That West Virginia coal miners and recent college graduates in New York City both voted for him makes perfect sense.

Class politics is back in a big way. Not because some socialist senator has made it so, but because the current economic and political conditions have made class a central issue among the American electorate.

In the heyday of the New Left many thought that the newly radicalized youth and student movement would replace the traditional working class as the revolutionary agent of social change. Today the two are largely one and the same.

Sanders has helped to galvanize and steer this newly class-conscious block of young working-class voters towards an emancipatory politics. Socialists should build on this momentum, developing this block into a committed social base for radical politics.