Red Teamsters

The radical teamsters of Minneapolis showed what democratic unionism looks like.

National Archives and Records Administration / Wikimedia Commons

It is no secret that the American worker is in trouble. Jobs are increasingly precarious, and real wages have been trending downward for decades. Unions, once strong and aggressive, now often seem to be in retreat, forced into a defensive conservatism. Barely one in ten wage earners pays union dues. 21 percent of the 14.5 million union members in the US live in two states, New York and California.

In many other regions of the country, trade unionism is a dirty word. The spirit and solidarity of the labor movement are pilloried as alien to the principles of a free (market) society.

To be sure, there are signs that many workers want to rebuild militant trade unionism. But how is this to be done? If we want to rebuild the labor movement, it’s first important to appreciate what workers accomplished in the past, and examine how they managed to win struggles in conditions that were arguably much worse than those confronting workers today. If we want to resurrect the political unconscious, Fredric Jameson’s injunction “Always historicize!” is an apt place to begin.

This year marks the eightieth anniversary of one of the most important class struggles in the history of the US labor movement. Over the course of seven months in 1934, Minneapolis teamsters waged three strikes. These historic battles set the stage for a new kind of trade unionism later in the 1930s. And, decades later, they are still relevant for a flagging labor movement.

Making a Union Town Against the Odds

In the 1920s, Minneapolis was dominated by reactionary, anti-labor employers. They were organized in a powerful body known as the Citizen’s Alliance, formed in the pre-World War I years. This Alliance blacklisted labor organizers; kept tabs on radicals; and hired spies, company guards, and stool pigeons. Strikes were crushed. Minneapolis was known as a haven for scabs.

Radicals understood the dimension of their defeat. In a 1920 Minneapolis May Day parade they decked out a donkey with a placard. “I and all of my relatives work in an open shop,” read the sign on the ass.

Yet by the end of 1934, Minneapolis was a union town. The seemingly all-powerful Citizen’s Alliance had been defeated.

The General Drivers’ Union (GDU), Local 574 of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters (IBT), was the unlikely engine of this transformation in class relations. With fewer than 175 truck-driving members scattered throughout small Minneapolis trucking and taxi companies in 1933, the GDU looked like anything but a vehicle of militant mobilization.

Local 574’s leadership was an ossified officialdom, hostile to militant action of any kind. Teamster International President Dan Tobin of Boston was an old-style American Federation of Labor (AFL) business unionist. Reluctant to sanction strikes, he lauded the respectability of his trucking fraternity, “craftsmen” Tobin regarded as superior to the unskilled immigrant and “colored” workers who toiled at unorganized, low-paying, and insecure jobs. Tobin did his best to insulate the Teamster ranks from the currents of radicalism that had been swirling around trade unionism for decades.

One of those currents was rooted in Minneapolis. At first, in the late 1920s and early 1930s, it seemed buried deep in the city’s coal yards. Few in number, these militants were shunned by the Teamster bureaucracy, kept out of the union, and attacked publicly as dangerous “reds.” They decided to constitute an informal organizing committee, composed of barely a dozen mostly non-union drivers and coal heavers.

From these inauspicious beginnings, the rebel contingent organized and led the 1934 strikes that changed the balance of class forces in Minneapolis. Membership in Local 574 burgeoned to seven thousand, and the union became a vibrant force. It headed up an eleven-state organizing drive that brought tens of thousands of over-the-road truckers into the labor movement, swelling the ranks of the national IBT to five hundred thousand by the early 1940s.

Revolutionaries Surface

The handful of radicals who charted this new course were a revolutionary bunch. Key figures among them had been members of the Industrial Workers of the World or the Socialist Party. Having grown frustrated with these bodies, they helped establish the Communist Party (CP) in the 1920s. The increasing Stalinization of the Communist International, and its reverberations inside the American party, sat uneasily with them, however.

In 1928–9, the Minneapolis dissidents criticized the Soviet Union-aligned CP, leading to their expulsion, en masse, from a party they had done much to build. They became part of a small Trotskyist movement centered in New York named the Communist League of America (CLA); the organization was renamed the Socialist Workers Party (SWP) in 1938.

The Minneapolis CLA was led by Carl Skoglund, a Swedish socialist who had immigrated to America in 1911 after organizing strikes and a mutiny of conscripted soldiers, and Vincent Ray Dunne, arguably Minnesota’s most public “red” throughout the 1920s. The Trotskyist duo grasped that organizing the transportation industry in Minneapolis was pivotal to reviving labor militancy in the doldrums of the Great Depression.

They knew the official IBT hierarchy, implacably conservative, would be of no help. So Skoglund, Dunne, and other CLAers went to work on their own. Talking union with their fellow workers, these militants drew a small number of workers into their inner circle. They widened discussions of longstanding grievances among discontented rank and file workers, both union members and unorganized laborers.

From these small beginnings grew working-class awareness that there was an alternative to the local IBT bureaucracy. All could have been squandered, however, if this volunteer organizing committee had jumped the gun, calling a strike precipitously and leading the workers to defeat. Indeed, as Dunne was fired from his job at a fuel distribution depot at the end of the 1933 coal season, the employers tiring of his public presence in protests of the unemployed, there were calls for a walkout. Dunne and Skoglund knew that spring (with coal deliveries dropping off to nothing) was not the time for a confrontation with the bosses.

The Trotskyist agitators continued their work among the teamsters. They further consolidated relations with disgruntled workers, but they also developed an adroit strategy of neutralizing the local IBT bureaucracy. First, the Trotskyist militants cultivated close working relationships with two non-CLA IBT officials who exhibited a fighting spirit, winning them over to their perspective. Second, they also secured a seat on Local 574’s executive board, getting Dunne’s brother a paid position within the GDU local, where he pressed the elementary need for workers to be prepared for possible job action.

As Farrell Dobbs would later note, “the indicated tactic was to aim the workers’ fire straight at the employers and catch the union bureaucrats in the middle. If they didn’t react positively, they would stand discredited.” All of this pushed conservative labor leaders into corners where they were forced to at least give lip service to building the kind of fighting trade unionism that they actually abhorred. This, in turn, whet the appetite for change among the workers in the industry, both organized and unorganized.

One result of this was that Local 574 actually endorsed a strike vote with a mere thirty-four union members present. Soon, however, meetings promoted by the volunteer organizing committee were drawing hundreds of boisterous workers. They demanded militant action, not the usual IBT slumber parties.

A First Strike

Some of the most pivotal of these “alternative” union meetings were scheduled on Sunday afternoons, secure in the knowledge that IBT bureaucrats would not attend. They agitated among the workers to get a sense of what the strike demands should be and promoted the need to wrestle concessions from the bosses.

The walkout finally came during a cold stretch in February 1934. With the companies needing to get fuel to customers’ furnaces, Skoglund and Dunne understood that the teamsters tasked with delivering the coal had some leverage.

On the day of the strike, the militant leaders locked their trucks inside the coal yards. Picket captains had been chosen, and they were provided with mimeographed instructions outlining the tasks and responsibilities of strike leaders. Given the large number of work sites scattered throughout the city, pickets needed to be mobile. Coal trucks and automobiles were commandeered to form “flying squadrons.” They headed off scab trucks, seized them, and dumped their loads in working-class neighborhoods; scavengers quickly gathered up the free coal.

Within hours, sixty-five of the sixty-seven coal yards in Minneapolis were closed, and 150 coal dispatching offices had been shut down. The mainstream IBT leaders, the coal bosses, and the trucking enterprises were all dumbfounded. None had anticipated the strike’s dramatic effectiveness.

The owners conceded after two and half days, and the GDU accepted a partial victory in which wages were increased modestly. More importantly, the bosses were forced to acknowledge the union during an actual strike, something that had not happened in over twenty years.

Organizing Workers to Win

In the aftermath of the February 1934 strike, the CLA revolutionaries effectively took over Local 574. They had won the workers’ respect in an actual battle with the bosses. They had also built a critical beachhead inside the IBT local, consolidating relations with those few Teamster officials who actually wanted to extend unionism in Minneapolis and promote class struggle. From this base of control, the CLA created an infrastructure that could nurture and sustain rank-and-file militancy.

The result was two strikes in May and July. Much larger and more protracted than the February walkout, they were planned down to the last detail. But the stakes had changed. The principal battle of these class struggles was over a new kind of inclusive industrial unionism.

A decisive difference between the Tobin-led IBT bureaucracy and the CLA-led Minneapolis General Drivers’ Union was that for the militants the 1934 strikes were fought to encompass all workers in the industry. Local 574 would be built by fighting — against both bosses and union bureaucrats — to include all of those who moved goods, loaded trucks, and prepared produce in Minneapolis’s market and warehouse districts.

To further marginalize their cautious opponents among the trade union tops, who wanted nothing to do with mass unionism in the trucking sector, the CLA leadership created a “Strike Committee of 100” that dwarfed the remaining reluctant GDU bureaucrats. CLA members and advocates now staffed all of the smaller, and critically important, organizing and negotiating committees.

The employers and their allies fought back viciously, relying increasingly on the Citizen’s Alliance. Municipal and state power was quick to rally to the side of law and order.

The mayor backed a vindictive police force led by a chief determined to crush the workers and willing to execute strikers and strike supporters in the street if necessary. “You have shotguns, and you know how to use them,” Police Chief Johannes instructed his officers in July 1934.

A picket captain described the police carnage in one infamous battle, memorialized as “Bloody Friday”: “They just went wild. Actually they shot at anybody that moved. … they kept on shooting until all the pickets had either hid or got shelter somewhere. Oh, they meant business.” Novelist Meredel Le Sueur’s account was more gruesomely lyrical: “[T]he cops opened fire.. . . men were lying crying in the street with blood spurting from the myriad wounds buckshots make. Turning instinctively for cover they were shot in the back.. . . Not a picket was armed with so much as a toothpick.”

Two workers died on “Bloody Friday”: Henry Ness, a striker, riddled with buckshot, succumbed to his wounds almost immediately. John Bellor, an unemployed strike supporter also critically injured in the battle died, days later. Forty thousand lined the streets and marched in Ness’s funeral procession.

To add insult to injury, Governor Floyd B. Olson, in spite of proclaiming himself a friend of the worker, called the National Guard into the increasingly stormy picture, arresting the strike leaders and taking over union headquarters.

Strike leaders were prepared for such opposition. They developed an extensive intelligence network of secretaries working for various enterprises who explained what the trucking magnates were preparing for next. The union took to the skies and the streets. It enlisted an airplane to promote labor’s cause with airborne banners and a squad of teenaged motorcyclists to courier strike leaders reports of goings on throughout Minneapolis.

Eventually, as the July-August strike made class war the central drama in the city, dividing Minneapolis irrevocably into camps of pro- and anti-strike, the CLA leadership started a daily strike newspaper, the Organizer, staffed by an experienced Trotskyist cadre from New York.

The union set up its headquarters in a block-long vacant garage. The “nerve center” of strike headquarters was a bank of telephones staffed by volunteers. Into this phone bank flowed calls from picket captains across a designated fifteen city districts, outlining conditions and appealing for help if it was required. A short-wave radio was used to monitor police communications. Dunne and Dobbs then oversaw the dispatching of pickets.

A commissary was outfitted. Farmers donated food for the kitchen, outfitted to feed five thousand workers a day. Cooks lined up to prepare meals. A makeshift hospital was established in a section of the headquarters to care for wounded workers and their supporters. Sympathetic doctors and nurses staffed the facility on their off hours. An unemployed workers organization was established; those in its ranks were made honorary members of the GDU.

A women’s auxiliary attracted wives and daughters, mothers and aunts. All helped build the union. Integrated into the struggle, these women served meals, sandwiches, and coffee to the strikers; distributed the union newspaper; raised funds; marched on city hall; and even fought, clubs in hand, on picket lines.

Local 574 was also made into a model of democratic procedure and open discussion. Regularly convened mass meetings kept the membership apprised of strike developments. When they actually secured paid union positions after their 1934 strike victories, the Trotskyists guiding the teamsters’ insurgency changed the salary scales for Local 574 functionaries, ensuring that union officials were paid no more than those working in the industry.

In the end the workers won, and they won big. Unionism was secured in Minneapolis. Wages rose, to be sure, and conditions on the job improved. But perhaps even more importantly, unionists saw themselves and the world differently. The possibilities of what collective struggle and solidarity could achieve now factored into how workers understood their lives.

Class War Warriors and the Red Scare

All of this left the bosses apoplectic. Local 574 and its Trotskyist leadership were vilified in the mainstream newspapers. Anti-communism blanketed Minneapolis in 1934 like a dense fog.

Employers and their sociocultural allies no doubt drove the city’s Red Scare that year, but conservative labor leaders like Tobin also contributed. One striker wrote to the Organizer that as “a member of 574,” he was “a Chippewa Indian and a real American,” “not a communist,” but he deplored the way in which certain IBT leaders were adding “fuel to the fire” with their persistent red-baiting.

A leading member of Local 574 was Ray Rainbolt, a Sioux Nation trucker who credited Dunne with recruiting him to labor’s cause. Rainbolt went on to play a decisive role in the 1934 strikes, serving on a number of crucial committees and facing off against Governor Olson.

In the later 1930s, Rainbolt joined the SWP and headed up the Union Defense Guard (UDG). This body formed when fascists known as the Silver Shirts threatened to organize in Minneapolis. The Silver Shirts understood the importance of infiltrating the now-powerful unions, making them nurseries of recruitment to the Right, and replacing class-based understandings of the social order with their pernicious racism and antisemitism. Rainbolt, who had military experience in World War I, drilled the rifle-bearing trade unionists of the UDG, training them in the event of a reactionary attack that never materialized.

Extending the Meaning of Local Struggle

Minneapolis was not the only hot spot in the 1934 class war. Other strikes, including those waged by Toledo auto-parts workers and San Francisco longshoremen, were also momentous battles. They, too, were led by “reds.” But their leaderships were neither as embedded within the locale and its particular industry, nor as successful, as the Minneapolis Trotskyists.

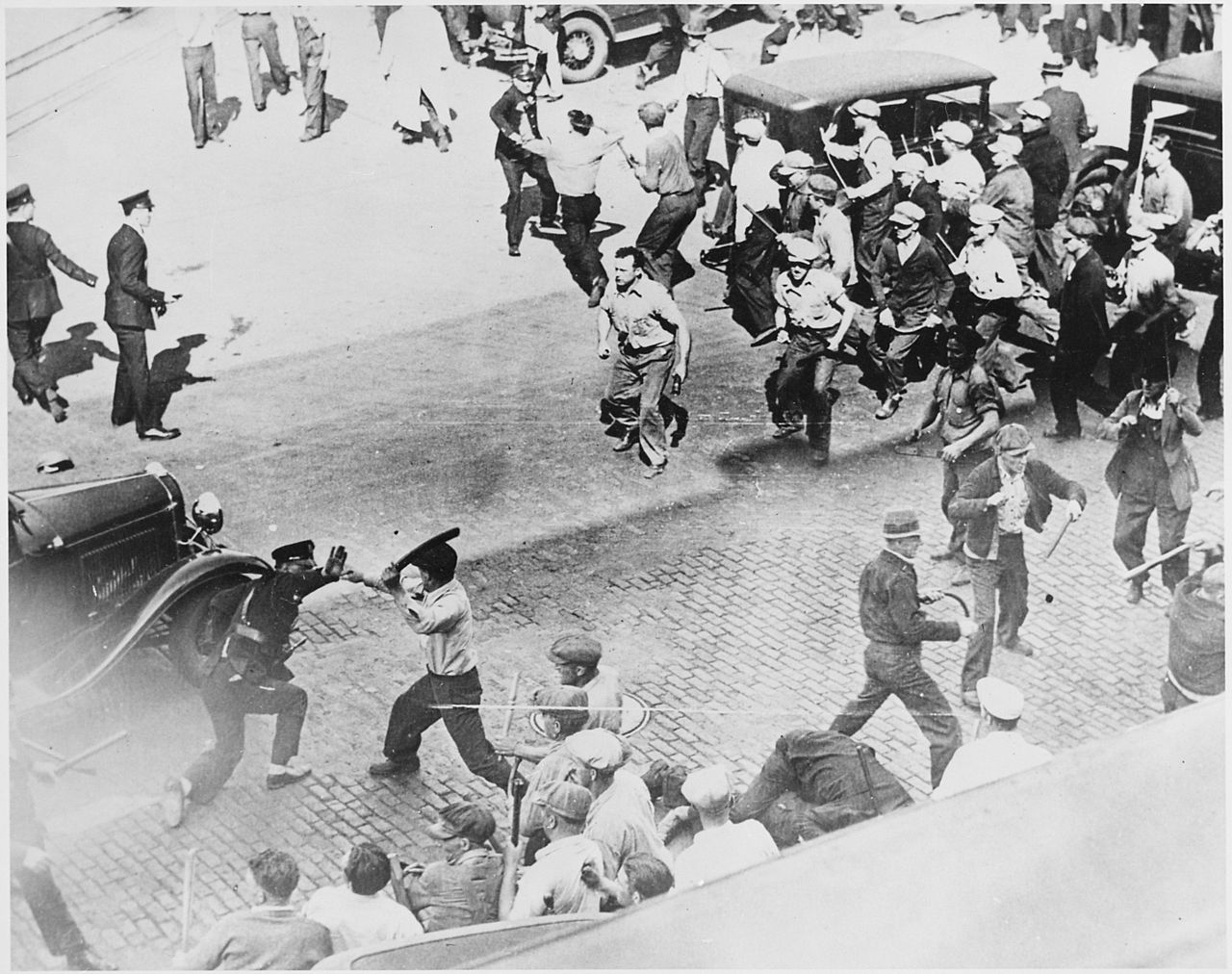

The Minneapolis strikes erupted at a time when the American labor movement was poised to take an important step forward. In theaters across the United States, millions saw film shorts showing workers, police, and Citizen’s Alliance-recruited “special deputies” fighting in the streets of the Minneapolis market district. Working-class audiences saw Minneapolis laborers responding to violence — not with submission, but with resistance.

At the May 22 “Battle of Deputies Run,” strikers had routed the 1,500 “special deputies.” Described as a rag-tag assembly of “salesmen, clerks, and patriotic golfers” whipped into a frenzy against “red dictators,” the Citizen’s Alliance anti-strike recruits also included university fraternity “boys,” paid thugs, playboys, and socialites, including some who came to picket lines in jodhpurs and polo-hats or cleated mountaineering boots (not the best footwear for a fight in alleyways paved with cobblestones).

Two of their number — Citizen’s Alliance attorney, local businessman, and pillar of respectable Minneapolis society, Arthur Lyman, and a marginal “penny capitalist” in the wood-hauling sector, Peter Erath — succumbed to injuries sustained in a deadly market clash with strikers already embittered by police brutality.

Meridel Le Sueur wrote of an “emergent world . . . coming from the past . . . into the future. . . . It is the point of emerging violence . . . the point of departure of growth.”

United Mine Workers of America leader John L. Lewis saw the strike similarly. As one of Lewis’s early biographers, Saul Alinsky, wrote in 1947, when “Blood ran in [the streets] of Minneapolis,” it got the burly, idiosyncratic head of the miners union to sit up and take notice.

Lewis was no friend of militant, democratic labor organization, but he could still appreciate that the moribund unionism of the AFL needed to be revitalized. The Congress of Industrial Organization (CIO) mass production unionism that Lewis would soon advocate was thus born of the insights and activities of the Minneapolis CLA leaders and the struggles of the militant rank and file that they mobilized.

A Revolutionary Leadership’s Day in Court

For all the success of the Minneapolis workers’ revolt of 1934, its achievements would not be allowed to survive into the post-World War II era. Workers following the leadership of Trotskyists, beating back bosses and trade union bureaucrats and, in the face of fascist threat, arming themselves in a Union Defense Guard, certainly caught the attention of powerful opponents.

As these same workers brought the lessons of Minneapolis into the IBT interstate organizing drive of the late 1930s, the Justice Department, the Federal Bureau of Investigation, the employers, a newly elected Republican governor of Minnesota, the IBT bureaucracy (with a young and later to be infamous Jimmy Hoffa playing a leading role), and even left-wing rivals such as the Communist Party, colluded during World War II to displace and defeat the Trotskyists in the Minneapolis Teamster leadership.

Using the notorious 1939 Smith Act, which stifled dissent by labeling it treason, the state relied on the war climate of 1940–3 to haul twenty-nine SWP members and Minneapolis Teamster leaders into court on trumped-up charges; eighteen, including much of the leadership of the US Trotskyist movement, were railroaded to jail.

Tobin and the IBT bureaucracy, relying on state labor union certification boards, sweetheart contracts with employers, and bands of Hoffa-led thugs, attacked the Minneapolis local in the courts and on the streets. Driven out of the AFL and into the CIO, and then forced to concede that it could not sustain a union against recalcitrant employers, the state, and the official Teamster bureaucracy, the Trotskyists who had reinvigorated unionism in Minneapolis were forced to abdicate their positions of leadership to the Tobin/Hoffa forces. It was a sorry denouement.

Remembering 1934

Those who wish to rebuild the labor movement can learn — and in some cases, have learned — from the Minneapolis events of 1934.

The Chicago teachers’ strike of 2012, for instance, originated in a small organizing committee of militants who managed to bring a union that had avoided overt class struggle since 1987 into an epic confrontation with a neoliberal mayor. Not surprisingly, the Caucus of Rank-and-File Educators, on the way to this successful mobilization, held reading groups for organizers that focused on Farrell Dobbs’s account of the 1934 strikes, Teamster Rebellion.

From the Occupy movement to the protests in Wisconsin, from the minimum-wage victories in Seattle and elsewhere to the struggles to organize Walmart, workers are showing they are capable of fighting to win and that class struggle is, once again, on the agenda.

But most of these current fights, as crucially important as they are, remain weakened by a lack of the kind of political leadership that guided the 1934 strikes in Minneapolis. Decades later, a member of the “Strike Committee of 100” recalled: “The rank and file was really the power of the whole movement, but they still needed that leadership to lead them. I don’t care how good the army is, without a general they’re no good.” The struggle for trade-union revival in the age of neoliberal capitalism is simultaneously the struggle to rebuild the revolutionary left.

The Minneapolis Trotskyists provide an example of what that left might look like. They were not, contrary to Citizen’s Alliance red-baiting, making “Revolution in Minneapolis” in 1934. Their aim was far more modest. They wanted to build democratic, mass-production unionism, creating a defense for the working class against the worst excesses of capitalist exploitation and transcending the narrow job-trust conception of labor organization promoted by Dan Tobin and his ilk.

In their militant and principled refusal to succumb to business unionism, the leaders of the Minneapolis strikes built important bridges to radical possibility. It was this dogged militancy that impelled the state and capital, aided by conservative unionists, to attack and marginalize the leadership of the 1934 Minneapolis strikes and its understanding of how trade unionism in the US could be rebuilt.

Eighty years later, these strikes, with their lessons about the capacity of workers to fight even in bad times, still live for us as a pathway to possibility.